Do you know as much as your doctor about nutrition? Unfortunately, you might actually know more than your doctor about nutrition. Many would scoff at that notion, not realizing that the majority of practicing physicians don’t actually have any nutrition training at all. When I attended medical school, the sum total of nutrition training during that 4 years was about 2 hours. That means a lay person could take a weekend nutrition class at a community college or public library and actually get more nutrition training than a great many doctors. Let’s see what the published studies tell us about this important issue…

Despite the connection between poor diet and many preventable diseases, only about one-fifth of American medical schools require students to take even a single nutrition course, according to Dr. David Eisenberg, adjunct associate professor of nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“Today, most medical schools in the United States teach less than 25 hours of nutrition over four years. The fact that less than 20 percent of medical schools have a single required course in nutrition, it’s a scandal. It’s outrageous. It’s obscene.” (1, 2) -Dr. David Eisenberg, M.D., adjunct associate professor of nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

We should be adding more nutrition courses in medical schools as time goes by, but it’s apparently becoming less. In this 2010 published study of all 127 accredited U.S. medical schools, only 25% required a dedicated nutrition course back in 2010, whereas it’s reported above in 2019 to now be less than 20% (3).

Medical schools should place a greater emphasis on meaningful nutrition education, according to a new Viewpoint article in JAMA co-authored by Dr. Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The March 2019 article noted that, on average, medical schools devote only 19 hours of a four-year curriculum to nutrition. Moreover, medical schools tend to focus on nutrition topics such as vitamin deficiency states, which is shortsighted given that diseases related to vitamin deficiencies aren’t a major problem in the U.S. Even after medical school, clinicians have very little exposure to nutrition-focused education throughout their careers, according to the article.

“Beginning with medical school, the time devoted to nutrition is limited, with an average of 19 total hours over 4 years, and is focused largely on biochemistry and vitamin deficiency states…Following medical school, nutrition education during the 3 or more years of graduate medical education is minimal or, more typically, absent…The problem is that, currently, most physicians do not have enough education in nutrition to contribute meaningfully…At minimum, physicians need sufficient training to at least begin the nutrition conversation with their patients.” (4)

In this study of all 127 accredited U.S. medical schools, on average, U.S. medical students received only 19.6 contact hours of nutrition instruction during their medical school careers. This equates to less than 1% of all the estimated total lecture hours. (3)

More importantly, the majority of this minuscule educational content relates to biochemistry and not diets or practical, food related nutritional decision making.

“In New Zealand’s largest medical school…Students receive approximately twenty hours of nutrition teaching, similar to the United States national average of 19.6 hours.” (5)

“Medical education must be brought up to date. For physicians to be ill trained in the very area most impactful on the rate of premature death at the population level is an absurd anachronism.” (6)

– Dr. David L. Katz, MD, MPH, Director, Yale University Prevention Research Center

“Unfortunately, there are few external incentives to improve nutrition education in medical school…At the postgraduate level, with regard to board certification exam requirements for internal medicine certification, the word “nutrition” is not mentioned in the required proficiencies.” (7)

This article also noted how cardiology fellows don’t need to complete even a single requirement in nutrition counseling.

“The teaching of Clinical Nutrition (CN) is frequently neglected in Medical Schools…” (8)

Dr. David L Katz of Yale University recently addressed the issue with medical school curriculum.

“The reason for the prevailing deficiency in medical education is a matter of history and failure to keep pace with changes in epidemiology. The basic structure of the medical school curriculum in 2018 still rests on the foundation of the Flexner Report compiled in 1920…a model that fails utterly today. Perhaps relegating the training of physicians to an educational model a century old is itself an ethical lapse?” (6)

Why can’t we just add more courses in nutrition?

“Course masters jealously guard lecture time and topics to prevent losing their influence within the medical community. Therefore, adding a large number of lectures to existing courses or adding a new course to the curriculum is very difficult.” (9)

“To help patients access credible information and make informed lifestyle choices, clinicians must be able to do so themselves, yet the topic to date receives little attention in medical education.” (6)

“The teaching of Nutrition in schools of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing is most inadequate at the present time and is almost non-existent in many schools. The number of specialists in Nutrition among physicians, dentists and nurses is very limited and even in the United States, a few hundred persons would be an optimistic estimate.” (10)

For several decades, many articles (11, 12), conferences (13, 14, 15, 16, 17), and even congressional hearings (18) have called to increase nutrition education in medical schools. However, most medical schools in the United States still do not have a specific nutrition course in their curriculum (19). Most students enter medical school eagerly expecting some attention to be given to nutrition (20), but most feel that their nutrition education is very inadequate (21).

Congress is concerned about the lack of nutrition training in Medical Schools.

“The Congress has had a long-time concern about the adequacy of nutrition education provided medical students and physicians during their training. Attempts over three decades to address this deficiency have been largely ineffective… There exists substantial institutional and structural inertia against incorporating a substantively larger amount of nutrition into the overcrowded medical school curriculum.” (18)

Medical students spend many hours learning and memorizing the complexities of cellular metabolism, biology and function in health and disease. But very little effort is given to the practical application of these facts in assessing and managing the nutritional needs and problems of patients. How seriously do medical schools and hospitals take nutrition anyway?

Since 63% of all medical schools maintain at least one fast food franchise at their affiliated hospitals, how can doctors be expected to learn and promote good nutrition? (22)

In this study, 38% of the top 16 hospitals in the United States had fast food establishments. (23)

It was reported that 9% of children’s hospitals (including academic and non-academic) in North America had brand name fast food franchises. (24)

“Fifty-nine of 200 hospitals with pediatric residencies had fast food restaurants.” (25)

With so many hospitals having little to no nutrition education and fast food franchises onsite, what is the real goal here? Is it the health, welfare and benefit of patients, or is it the profitability of such businesses? Perhaps the selling of high-calorie, nutrient deficient fast food in the same place where the most seriously ill are treated isn’t such a great idea.

A large study of senior medical students was conducted and the results were very disturbing.

“Eighty-five percent were dissatisfied with the quantity and 60% with the quality of their medical-nutrition education.” (22)

“Future doctors had positive attitudes towards nutrition care but showed important knowledge gaps and also felt inadequate in their confidence to provide nutrition care.” (26)

“Though students considered nutrition care as an important role for doctors they felt incapacitated by non-prioritisation of nutrition education, lack of faculty for teaching of nutrition education, poor application of nutrition science and poor collaboration with nutrition professionals.” (27)

“The majority of graduating US medical students reported inadequate nutrition training over the past decade.” (28)

“The perceived relevance of nutrition counseling by US medical students declined throughout medical school, and students infrequently counseled their patients about nutrition.” (29)

“The amount of nutrition education that medical students receive continues to be inadequate.” (3)

” Studies in the US have described nutrition education within medical degrees as insufficient…resulting in nutrition education ranging across medical programmes from none, to short lectures…” (30)

“It is argued that the amount of nutritional education in the teaching curricula of different medical schools remains inadequate and does not meet the needs of this important area of health sciences. Hence, many studies show that family physicians generally have little training in nutrition.” (31)

When it comes to getting residency, it appears that nutrition education isn’t very important anyway.

The current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Program Requirement document for internal medicine residency has 42 pages, and the document for cardiovascular disease fellowship has 41 pages, but neither document includes the words “nutrition” or “diet.” (32)

In spite of the lack of nutrition education, it’s been demonstrated that the majority of patients feel that physicians should provide counseling on healthy nutrition. (33)

BUT,

Nearly every published study on the issue of nutrition counseling by doctors shows that family physicians, although supportive, are not delivering nutrition services to their patients (34, 35).

“Physicians report that they have not had adequate preparation (36) for their role as promoters of good nutrition”. (37, 38)

“Unfortunately, a wide gap exists between the public’s need for accurate and sensible dietary information and the availability of such advice from physicians.” (35)

1,030 Physicians were questioned in this study, and only 58% of the respondent physicians said they had received any nutrition training AT ALL. That means 42% had received NONE.

As such, the study author noted that physician lack of confidence in counseling skills was an important barrier to providing dietary counseling. This is understandable since nearly half of the physicians had received no nutrition training at all.

Once in practice, fewer than 14% of physicians believe they are adequately trained in nutritional counseling. (39) This is no surprise since most get no training whatsoever.

“The level of nutritional knowledge and nutritional skills among the various specialties and subspecialties of medicine and surgery is not commensurate with the role and importance that nutrition has been shown to play in the etiology and management of the most common diseases that now afflict society…” (40)

“Unfortunately, healthcare providers, and I’ve been one, rarely say anything about how to eat a healthy diet. We physicians like to write drug prescriptions for drugs and do procedures.

But, I was just at an international meeting of cardiologists and asked how many of them knew what their patients were eating, and zero raised their hand. That’s a sad commentary on how we practice medicine.” – Dr. Walter C. Willett, M.D., Dr. P.H., Chair of Nutrition, Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“The clinical nutritional knowledge of medical students and practicing physicians was assessed. Overall, nutrition knowledge was modest. However, there were substantial variations in knowledge among closely related topics. Knowledge often was highest among nutrition topics which have received the most publicity in the popular press. The nutrition knowledge profile suggests that medical students and physicians learn about nutrition haphazardly and are highly dependent for their knowledge on nonprofessional literature.” (41)

“Many clinicians feel ill-informed on nutritional issues. While they are well aware that type 2 diabetes is not caused by a metformin deficiency, they are hard-pressed to know how to tackle the food habits that are at its core.” (42)

“Physicians recognize that they lack the education and training in medical nutrition needed to counsel their patients and to ensure continuity of nutrition care in collaboration with other health care professionals.” (40)

But apparently, many still promote their expertise on the subject where none exists.

Dr. David L Katz of Yale University addressed artificial expertise regarding diet in a clinical setting in the AMA Journal of Ethics. Basically, just because doctors eat, that doesn’t make them experts in nutrition, and offering an “expert” nutrition opinion without legitimate expertise, is an ethical breach.

“There is the universal familiarity with diet that fosters contempt not for diet, of course, but for nutritional expertise. (43) Physicians with no genuine expertise in, say, neurosurgery are neither likely to broadcast detailed opinions on that topic nor to have their “expert” opinions solicited by media. Most topical domains in medicine enjoy such respect: we defer expert opinion and commentary to actual experts. Not so in nutrition, where the common knowledge that physicians are generally ill trained in this area is conjoined to routine invitations to physicians for their expert opinions on the matter. All too many are willing to provide theirs, absent any basis for actual expertise—such as specialty training in nutrition, published research in that area, or clinical experience in dietary counseling—and this, too, is an ethical lapse. In a culture that routinely fails to distinguish expertise from mere opinion or personal anecdote, we physicians should be doing all we can to establish relevant barriers to entry for expert opinion in this, as in all other matters of genuine medical significance.” (6)

So, if you’re not an expert, you shouldn’t act like one and offer up your “expert” opinion, even if you are a doctor.

“It is impossible for anyone to begin to learn what he thinks he already knows.” – Epictetus, Greek Philosopher

“Physicians should treat nutrition like all other content areas in medicine and leave expert opinion to those with some valid claim to expertise…” (6)

Do family doctors even want to promote nutrition to their patients?

It’s been reported that only 21% of family physicians experience personal gratification in counseling patients about diet issues (44).

Changing the status quo.

Aside from the widespread lack of training and knowledge regarding clinical nutrition, one of the most significant barriers for widespread adoption of effective nutrition counseling for doctors is compensation and monetization. In the healthcare business, doctors are typically compensated based upon interventions. Evidence shows us that disease management is the foremost goal. If a patient is given dietary advice for health conditions instead of a prescription, this is looked upon as a business mistake in typical healthcare because of the lack of ongoing monetization. The reasoning is that the recurring prescription or billable revenue of ongoing long-term treatment is at risk if nutritional medicine advice is given with the objective of curing or significant betterment of the patients’ condition. The healthcare system is geared towards intervention and not prevention.

How widespread is the nutrition problem anyway?

Three-quarters of health care dollars are spent on preventable chronic lifestyle-related diseases. (45) Diabetes alone is estimated to cost the United States $245 billion per year. (46) Back in 1960, U.S. diabetes rates were only 1% of the population, with the vast majority of those cases diagnosed as type 1 diabetes. (47) According to the CDC, 9.3% of U.S. citizens are now diabetic, with the overwhelming majority suffering from type 2 diabetes, which is known to be a lifestyle disease, primarily of dietary origin. (48)

So, if we as doctors are really concerned about healthcare at the societal level, why is it getting so much worse? I think that the lack of nutrition training in medical school is directly implicated in a significant number of health problems related to nutrition.

The role of diet in the prevention and treatment of disease is beyond scrutiny. The 1988 U.S. Surgeon General’s first Report on Nutrition and Health demonstrates that improper diet is implicated as a significant causative factor in 5 of the 10 leading causes of death in the U.S. (49)

“The estimates vary, but it appears that there is a nutrition related reason for at least 25% of all office visits to primary care providers.” (50)

“Failure to address the contributions of food to health in the clinical context is an ethical lapse.” (6)

“Despite good clinical and epidemiologic evidence that a poor diet over long periods of time represents a high risk factor for these diseases, medical students are not receiving adequate information to translate this knowledge into practical advice regarding healthier diets for their patients.” (9)

“There is a nutrition-related reason for ≥25% of all visits to primary care providers.” (36)

In the United States, the primary causes of premature adult deaths are related to unhealthy behaviors, such as poor diet and lack of physical activity (15.2%). (51)

I am a steadfast advocate of nutrition centered medicine. It just makes sense to me personally and scientifically. Yet, there are numerous instances in medicine when individuals or groups who advocate nutritional interventions or lifestyle modifications as a means of preventing or even treating disease have met with indifference, hostility, denigration, or even the illegal forced closure of their facility by the medical establishment, such as what happened to me. The wheels of change in big medicine turn very slowly.

For example, when the tide was turning against smoking and cigarettes in the late 1940’s, the Editor in Chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association remained indignant and proclaimed in that very medical journal that “more can be said in behalf of smoking as a form of escape from tension than against it.” (52)

Dr. Fishbein later worked for the cigarette industry in the promotion of cigarettes. (53)

As recently as 1987, the Journal of the American Medical Association was perpetuating bad nutrition advice when they promoted their long-standing belief that, “Healthy adult men and healthy adult nonpregnant, nonlactating women consuming a usual, varied diet do not need vitamin supplements.” Most people, it was believed, could obtain adequate amounts of these nutrients from their diet, which is simply not the case. (54)

In 2002, it came as no surprise when the AMA finally reversed their erroneous policy on vitamin supplements by announcing that the Journal of the American Medical Association would begin advising all adults to take at least one multivitamin each day.

According to Drs. Fletcher and Fairfield of Harvard University who wrote JAMA’s new guidelines, “most people do not consume an optimal amount of all vitamins by diet alone…Recent evidence has shown that suboptimal levels of vitamins, even well above those causing deficiency syndromes, are risk factors for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and osteoporosis…The high prevalence of suboptimal vitamin levels implies that the usual US diet provides an insufficient amount of these vitamins. We recommend that all adults take one multivitamin daily.” (55)

In medicine, it often takes decades for the facts to win out over misconceptions and biases. After all, the widespread sale and use of cigarettes in hospitals was STILL happening just 30 years ago! (56)

We need to supplement because our food crops simply aren’t as nutritious as they used to be.

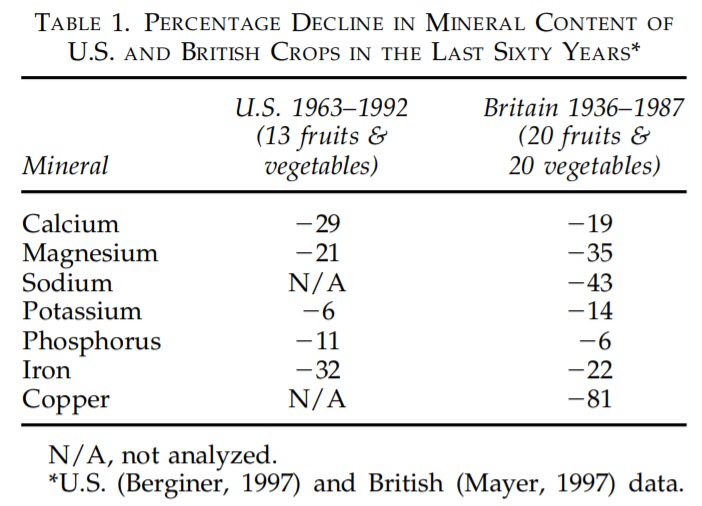

Four different analyses of U.S. and British nutrient content data have shown a decline in the vitamin and mineral content of fresh fruits and vegetables over the last 60 years (57, 58, 59, 60). Average declines in nutrient content are shown in Table 1.

Using government data, British research compared the mineral content of 20 fruits and vegetables between the 1930s and 1980s using government data. Marked reductions were found in calcium, magnesium, copper (down a massive 80%) and sodium in the vegetables. Fruit was lower in magnesium, iron, copper and potassium. (59)

“There were significant reductions in the levels of Ca, Mg, Cu and Na, in vegetables and Mg, Fe, Cu and K in fruits.” (59)

“New research indicates that the vitamin and mineral content of apples, oranges, and other ordinary fruits has declined on average 25 to 50% during the last generation.” (60)

“Several studies of historical food composition tables show an apparent decline in food nutrient content over the past 70 years. This decline has been attributed to soil degradation and the “mining” of soil fertility by industrial agriculture.” (61)

University of Texas research compared the nutrient content of 43 garden crops between 1950 and 1999. Of the 13 nutrients analyzed using US Department of Agriculture (USDA) data, the researchers observed significant declines in protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, vitamin B2 and vitamin C. For example, celery had 42% less protein; cauliflower had half as much B1; the B2 content of kale had fallen by 50%, and the vitamin C content of asparagus dropped by nearly two-thirds. (62)

Does your doctor say organic is the same as non-organic?

“Organic crops contained significantly more vitamin C, iron, magnesium, and phosphorus and significantly less nitrates than conventional crops.” (63)

Physician and New York Times bestselling author Dr. Michael Greger, M.D., writes that compared to conventional crops, “based on antioxidant phytonutrient levels, organic produce may be considered 20 to 40% healthier.” (64)

“Eat a healthy diet.” Does your doctor even know what that means? What does the AMA (American Medical Association) say about it?

“It is the consensus of the American Medical Association and the Association of American Medical Colleges that the vast majority of practicing physicians in primary and subspecialty care do not have an adequate font of knowledge to advise their patients on healthy diets.” (9)

“There is an urgent need…to create and implement comprehensive Lifestyle Medicine education for all health professionals, at all levels of training, worldwide.” (65)

“While the deficit of doctors’ nutrition knowledge and provision of nutrition advice is recognised, with barriers and challenges identified, there remains no clear path forward to address this issue.” (30)

Unfortunately, one of the biggest barriers to addressing the current nutrition education issue is the medical associations themselves.

Nutrition Education Mandate Introduced For Doctors

Medical Associations Opposed the Bill to Mandate Nutrition Training

California Medical Association Tried to Kill the Nutrition Bill

Nutrition Bill Doctored in the California Senate and rendered useless

How can we encourage doctors to learn nutrition, if the medical industry is actually resisting it from the point of medical school all the way to the trade organizations?

“Something’s got to give.”

“Physicians with appropriate training in nutrition can and should be a powerful force in providing accurate nutrition information and quality health care.” (66)

“Physician leadership is central to the credibility and success of nutrition interventions in health care.” (38)

“Practice must be evidence-based. Just as our prescribing practices must be founded on solid evidence, the same is true for dietary advice. Hunches, fads, and one’s own personal preferences are no basis for guiding therapy. Not only is there abundant evidence of the effectiveness of dietary interventions, there is also evidence regarding their acceptability.” (42)

“The mission of medicine is to protect, defend, and advance the human condition. That mission cannot be fulfilled if diet is neglected.” (6)

“The meteoric growth of the dietary supplement industry and consumer interest and spending in alternative therapies are viewed with frustration and also welcomed as opportunities by primary care physicians. The National Institutes of Health Center on Alternative and Complementary Medicine includes “Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle Changes” among its fields of practice, describing it as “the knowledge of how to prevent illness, maintain health, and reverse the effects of chronic disease through dietary or nutritional intervention.” (50)

“Not only do doctors require nutrition knowledge, they also require practical skills and guidance on how to integrate nutrition advice into their own practice.” (30)

“Medications are no substitute for dietary interventions. While medications can counter some of the effects of risky dietary habits, it is essential to address the underlying nutritional causes of diabetes, lipid disorders, and hypertension. Rather than viewing pharmacological interventions as “conventional” and nutritional interventions as “alternative,” these views should be reversed: Medications for these conditions should be considered “alternative” treatments when nutritional improvements have not gotten the job done.” (42)

We no longer have a healthcare system. We have vast disease care systems which include hospitals, clinics, diagnostic facilities, extended care facilities, pharmacies, and so on. Why is there all of this machinery involved in disease management and not directed at the most basic root of so many problems? Unfortunately, doctors are taught to think like doctors and not like investigators. I was trained to identify what disease would include the greatest number of this patient’s symptoms? I was not taught to investigate what nutrient deficiencies could be responsible. I was taught to identify the best prescription for the patient’s issue. I was not taught how to remedy the situation through good nutrition. The nutritional aspects of disease are rarely if ever questioned in “modern” medicine. A doctor only knows what they’ve learned thus far, and most are content just to get through school and get into practice so they can earn in their profession. A good doctor continues to study and learn more, beyond just the minimum of what’s required for licensure. That’s the kind of doctor I am. I spend time studying daily because I want to be the best doctor I can possible be. This is why I’ve studied clinical nutrition for 17 years. This isn’t about who is right, it’s about what is right when it comes to truly comprehensive patient care at the societal level. I’ve treated over 150,000 patients and I don’t know everything, not even close. But, I do know a that we are what we eat and drink.

References:

- Harvard University Website https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/doctors-nutrition-education/ accessed 4/4/2019

- https://youtu.be/JOT6yV9dt3E

- Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH.. Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: Latest update of a national survey. Acad Med. 2010;85:1537–1542

- Devries S, Willett W, Bonow RO. Nutrition Education in Medical School, Residency Training, and Practice. JAMA. Published online March 21, 2019.

- Crowley J, Ball L, Han DY, Arroll B, Leveritt M, Wall C. New Zealand medical students have positive attitudes and moderate confidence in providing nutrition care: a cross-sectional survey. J Biomed Educ. 2015:259653.

- Katz DL. How to improve clinical practice and medical education about nutrition. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(10):E994-1000.

- Eisenberg DM, Burgess JD., Nutrition Education in an Era of Global Obesity and Diabetes: Thinking Outside the Box. Acad Med. 2015 Jul;90(7):854-60.

- Guagnano, Maria & Merlitti, D & Pace-Palitti, V & Manigrasso, Maria & Sensi, S. (2001). Clinical nutrition: Inadequate teaching in Medical Schools. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases : NMCD. 11. 104-7.

- Walker WA. Advances in nutrition education for medical students – overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:865S–7S.

- Rana IA., Teaching nutrition in medical schools. J Pak Med Assoc. 1981 Oct;31(10):235-7.

- White JV, Young E, Lasswell A. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition-essential component of medical education. J Am Diet Assoc 1987;87:642–7.

- Winick M. Report on nutrition education in United States medical schools. Bull N Y Acad Med 1989;65:910–14.

- Aronson S. Medical education and the nutritional sciences. Am J Clin Nutr 1988;47:535–40.

- Swanson AG. 1990 ASCN nutrition educators’ symposium and information exchange: nutrition sciences in medical-student education. Am J Clin Nutr 1990;53:587–8.

- Nestle M. Nutrition in medical education: new policies needed for the 1990s. J Nutr Educ 1998;20:S1–29.

- Vitale J, Hodges RE. Symposium: teaching nutrition in medical schools. Am J Clin Nutr 1977;30(suppl):793–24.

- 1987 ASCN workshop on nutrition education for medical/dental students and residents—integration of nutrition and medical education: strategies and techniques. Am J Clin Nutr 1988;47:534–50.

- Davis CH. A report to Congress on the appropriate federal role in assuring access by medical students, residents, and practicing physicians to adequate training in nutrition. Public Health Rep 1994; 109:824–6.

- Feldman EB. Educating physicians in nutrition—a view of the past, the present, and the future. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;54:618–22.

- Weinsier RL, Boker JR, Morgan SL, et al. Cross-sectional study of nutrition knowledge and attitudes of medical students at three points in their medical training at 11 southeastern medical schools. Am J Clin Nutr 1988;48:1–6

- Weinsier RL, Boker JR, Feldman EB, Read MS, Brook CM. Nutrition knowledge of senior medical students: a collaborative study of southeastern medical schools. Am J Clin Med 1986;43:959–68.

- Lesser LI.. Prevalence and type of brand name fast food at academic-affiliated hospitals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:526–527 https://bit.ly/2UApatq

- Cram P, Brahmjee KN, Fendrick AM, Saint S. Fast food franchises in hospitals. JAMA 2002;287:2945–6.

- Lesser, L. Prevalence and Type of Brand Name Fast Food at Academic-affiliated Hospitals. J Am Board Fam Med September 2006, 19 (5) 526-527

- Sahud HB, Binns HJ, Meadow WL, Tanz RR (2006) Marketing Fast Food: Impact of Fast Food Restaurants in Children’s Hospitals. Pediatrics 118: 2290–2297.

- Mogre, V., Aryee, P.A., Stevens, F.C.J. et al. Future Doctors’ Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-Efficacy Regarding Nutrition Care in the General Practice Setting: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Med.Sci.Educ. (2017) 27: 481.

- Mogre, Victor et al. “Why nutrition education is inadequate in the medical curriculum: a qualitative study of students’ perspectives on barriers and strategies.” BMC medical education (2018).

- Mihalynuk TV, Coombs JB, Rosenfeld ME, Scott CS, Knopp RH. Survey correlations: proficiency and adequacy of nutrition training of medical students. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:59–64.

- Spencer EH, Frank E, Elon LK, Hertzberg VS, Serdula MK, Predictors GDA. Of nutrition counseling behaviors and attitudes in US medical students. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:655–62.

- Adamski, M. , Gibson, S. , Leech, M. and Truby, H. (2018), Are doctors nutritionists? What is the role of doctors in providing nutrition advice?. Nutr Bull, 43: 147-152.

- Hyska J, Mersini E, Mone I, Bushi E, Sadiku E, Hoti K, Bregu A. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices about public health nutrition among students of the University of Medicine in Tirana, Albania. SEEJPH. 2015;1:1.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Internal Medicine. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2017. Accessed February 4, 2019.

- Price, Mph James H. et al. “Patients’ expectations of the family physician in health promotion.” American journal of preventive medicine 7 1 (1991): 33-9.

- Soltesz KS, Price JH, Johnson LW, Tellojohann SK. Family physician’s views of the Preventive Services Task Force recommendation regarding nutritional counseling. Arch Fam Med 1995;4:589–93.

- Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med 1995;24:546–52.

- Kolasa, K., “Images” of nutrition in medical education and primary care, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 73, Issue 6, June 2001, Pages 1006–1009.

- Cimino JA. Why we can’t educate doctors to practice preventive medicine. Prev Med 1996;25:63–5.

- Glanz K. Review of nutritional attitudes and counseling practices of primary care physicians. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(suppl):2016S–9S.

- Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:287–298

- Lenders CM, Deen DD, Bistrian B, et al. Residency and specialties training in nutrition: a call for action. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5 Suppl):1174S–83S.

- N Podell, R & R Gary, L & Keller, K. (1975). A profile of clinical nutrition knowledge among physicians and medical students. Journal of medical education. 50. 888-92.

- Bernard ND. The physician’s role in nutrition related disorders: from bystander to leader. Virtual Mentor 2013;15:367–72.

- Nichols T. The death of expertise. Federalist. January 17, 2014. http://thefederalist.com/2014/01/17/the-death-of-expertise. Accessed April 27, 2018.

- Soltesz KS, Price JH, Johnson LW, Tellojohann SK. Perceptions and practices of family physicians regarding diet and cancer. Am J Prev Med 1995;11:197–204.

- Levy J, Segal LM, Thomas K, St. Laurent R, Lang A, Rayburn J.. F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America’s Future. 2013 Princeton, NJ Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–1046

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long-Term Trends in Diagnosed Diabetes, October 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/slides/long_term_trends.pdf Accessed January 30, 2014

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 29 million Americans have diabetes; 1 in 4 doesn’t know [CDC press release]. Tuesday, June 10, 2014. Accessed June 30, 2014 https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0610-diabetes-report.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Report on nutrition and health. Public Health Service. Washington: U.S. Govt Printing Office, 1988; DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 88-50210

- Kolasa, Kathryn. (1999). Developments and challenges in family practice nutrition education for residents and practicing physicians: An overview of the North American experience. European journal of clinical nutrition. 53 Suppl 2.

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1245.

- Fishbein, JAMA. 1948;138(9):652-653.

- https://drfarrahcancercenter.com/ama-american-medical-association/

- Vitamin Preparations as Dietary Supplements and as Therapeutic Agents. JAMA. 1987;257(14):1929–1936.

- Fletcher RH and Fairfield KM. Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults: Clinical Applications. JAMA, June 19, 2002; 287:3127-129.

- JAMA. 1985;253(20):2999-3000. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/398690

- Klein BP, Perry AK. Ascorbic acid and vitamin A activity in selected vegetables from different geographical areas of the United States. J Food Sci 1982;47:941–948.

- Bergner P. The Healing Power of Minerals, Special Nutrients and Trace Elements. Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing Co., 1997:46–75.

- Mayer AM. Historical changes in the mineral content of fruits and vegetables. British Food Journal. 1997;99:207–211.

- Jack A. America’s vanishing nutrients: Decline in fruit and vegetable quality poses serious health and environmental risks. 2005.

- Lyne, J. and P. Barak (2000). Are depleted soils causing a reduction in mineral content of food crops? ASA/CSSA/SSSA Annual Meeting. Minneapolis, MN

- R Davis, Donald & D Epp, Melvin & D Riordan, Hugh. (2004). Changes in USDA Food Composition Data for 43 Garden Crops, 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 23. 669-82.

- Worthington V. Nutritional quality of organic versus conventional fruits, vegetables, and grains. J Altern Complement Med 7: 161–173, 2001.

- https://nutritionfacts.org/2017/04/13/organic-versus-conventional-which-has-more-nutrients

- Polak R, Pojednic RM, Phillips EM. Lifestyle Medicine Education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2015;9(5):361–367.

- White JV, Young E, Lasswell A. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition-essential component of medical education. J Am Diet Assoc 1987;87:642–7.

The watching, interacting and participation of any kind and in any way with anything on this video, multimedia, article or page does not constitute or initiate a doctor patient relationship with Dr. Farrah®. None of the statements here have been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The products of Dr. Farrah® are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The information being provided should only be considered for education and entertainment purposes only. If you feel that anything you see or hear may be of value to you on this video or on any video or other medium of any kind associated with, showing or quoting anything relating to Dr. Farrah® in any way at any time, you are encouraged to and agree to consult with a licensed healthcare professional in your area to discuss it. If you feel that you’re having a healthcare emergency, seek medical attention immediately. The views expressed here are not medical advice, they are simply the viewpoints and opinions of Dr. Farrah® or others appearing and are protected under the first amendment.

Dr. Farrah® is a highly experienced Licensed Medical Doctor, not some enthusiast, formulator or medium promoting the wild and unrestrained use of herbs and nutrition products for health issues without clinical experience and scientific evidence of therapeutic benefit. Dr. Farrah® promotes evidence-based natural approaches to health, which means integrating her individual scientific and clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research as well as from the recommendations and experiences of respected experts. By individual clinical expertise, I refer to the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice.

Dr. Farrah® does not make any representation or warranties with respect to the accuracy, applicability, fitness, or completeness of any video or multimedia content provided anywhere at any time. Dr. Farrah® does not warrant the performance, effectiveness or applicability of any sites listed, linked or referenced to, in, or by any video content related to her, showing her or referencing her at any time.

To be clear, the video or multimedia content provided is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read or seen in any website, video, article or multimedia of any kind.

Dr. Farrah® hereby disclaims any and all liability to any party for any direct, indirect, implied, punitive, special, incidental or other consequential damages arising directly or indirectly from any use of this or any other video or multimedia content, which is provided as is, and without warranties.